Arcana

Arcana Italy 1972 colour

Director Giulio Questi Writers Giulio Questi, Franco Arcalli

Cast Lucia Bosé (Mamma), Maurizio Degli Esposti (Son), Tina Aumont (Brenda), Renato Paracchi

“The bones, the bladder..” whispers a midget into a young man’s ear, while a woman licks a doorway. Yes, I’m proud to say, it’s going to be one of those nights as we delve into the bizarre world of renegade Italian director Guilio Questi and his strangest film of all, the 1972 horror movie Arcana.

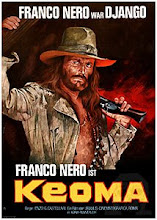

Questi is a fringe figure in Italian cinema, creating films which straddle the populist genre and elitist art divide and finding himself an outsider in both worlds. In a career since the Fifties he’s completed no more than five theatrical features, working in television and documentaries. A self-avowed anarchist, his radicalized politics is ever-present in his grimmest film, the apocalyptic spaghetti western Django Kill from 1967, and in his capitalist giallo thriller set on a chicken farm from 1968, the appropriately named Plucked!, or Death Laid An Egg. His is an uncompromising stance, and is thus: never let the audience, or a logical story for that matter, get in the way of the pursuit of one’s art.

Curiously, Arcana – on the surface his least political film - has dropped out of circulation since its 1972 premiere, and one can only wonder what a cine-literate Italian crowd weaned on Fellini’s eccentricities would have gleaned from it. The film starts off benignly enough in a Rome apartment occupied by a fortune teller. On the surface she’s a charlatan, milking good lire from her customers from carefully-staged group psychodramas – a kind of primal scream therapy, only with pissing and shitting – presided over by her freakishly insightful son Mario. He truly has inherited his mother’s divine gifts, but manifests them in more disturbing fashions. His myriad of unhealthy obsessions include dead animals or animal parts, visiting the subway tunnel his railway worker father died in, stealing photos and objects from his mother’s customers and creating elaborate charms with them, and crawling into bed with his mother or slicing her breast with a kitchen knife. A visit from a young woman engaged to an older man and worried about her future seals her fate, and in her Mario finds himself the perfect doll to stick his pin in. Figuratively speaking, of course.

Curiously, Arcana – on the surface his least political film - has dropped out of circulation since its 1972 premiere, and one can only wonder what a cine-literate Italian crowd weaned on Fellini’s eccentricities would have gleaned from it. The film starts off benignly enough in a Rome apartment occupied by a fortune teller. On the surface she’s a charlatan, milking good lire from her customers from carefully-staged group psychodramas – a kind of primal scream therapy, only with pissing and shitting – presided over by her freakishly insightful son Mario. He truly has inherited his mother’s divine gifts, but manifests them in more disturbing fashions. His myriad of unhealthy obsessions include dead animals or animal parts, visiting the subway tunnel his railway worker father died in, stealing photos and objects from his mother’s customers and creating elaborate charms with them, and crawling into bed with his mother or slicing her breast with a kitchen knife. A visit from a young woman engaged to an older man and worried about her future seals her fate, and in her Mario finds himself the perfect doll to stick his pin in. Figuratively speaking, of course.

The key is in the film’s title – arcane, or esoteric, or more specifically the major and minor arcana making up the deck of Tarot cards, used for divining and revealing hidden knowledge. The film, Questi states in the opening, is “not a story, but a game of cards”. Both the start and the epilogue, he continues, are not to be believed; as the film is spilt into two parts, like the Tarot itself, one might suspect that the entire narrative is a lie. “You are the player,” says Questi, suggesting everything contained herein has a hidden meaning to be decoded. “Play smartly and you’ll win.”

The key is in the film’s title – arcane, or esoteric, or more specifically the major and minor arcana making up the deck of Tarot cards, used for divining and revealing hidden knowledge. The film, Questi states in the opening, is “not a story, but a game of cards”. Both the start and the epilogue, he continues, are not to be believed; as the film is spilt into two parts, like the Tarot itself, one might suspect that the entire narrative is a lie. “You are the player,” says Questi, suggesting everything contained herein has a hidden meaning to be decoded. “Play smartly and you’ll win.”

Arcana is as much a horror film as David Lynch’s Eraserhead. While Lynch’s brand of nightmarish surrealism has found its way into post-modern pop culture, the eternal fringe-dweller Questi’s is of a much darker, more unsettling variety. Just when your feet are back on surer footing, the flowers start to die, the cards flip themselves over, children worship eggs or stick skewers in a bread homunculus, a donkey is hoisted up a building, and you are left the Hanging Man of the Major Arcana deck, caught halfway between revelation and damnation.

Arcana’s a rough ride, at times a Freudian avalanche-of-conscious imagery, and it’s in the second half the film veers off its rails and plows into much darker territory, past Fellini and into the domain of Bunuel, a universe of sex, death, politics, decay, deformity, and the “other world” which hangs over the film like a funereal veil. If you’re not a fan of demented art cinema of the Seventies, we’ll see you next week. For those with more metaphysical tastes, we invite you into the hidden world of Arcana.

Arcana’s a rough ride, at times a Freudian avalanche-of-conscious imagery, and it’s in the second half the film veers off its rails and plows into much darker territory, past Fellini and into the domain of Bunuel, a universe of sex, death, politics, decay, deformity, and the “other world” which hangs over the film like a funereal veil. If you’re not a fan of demented art cinema of the Seventies, we’ll see you next week. For those with more metaphysical tastes, we invite you into the hidden world of Arcana.